Amidst all the talk about democratization in the Middle East, one salient argument is that the economic development of otherwise disenfranchised people is key to the success of political and social reforms. By giving people an economic stake in the pursuit of happiness within their own societies, they would be less likely to turn to obscurantist, escapist, and xenophobic religious ideologies that spawn violent reactions and terrorism.

Yet there are many cultural and historical determinants that are at play in the evolution of the nations and countries of the Middle East, but which are more often than not swept under the rug for fear of raising controversy or offending sensitivities. However, the debate must be open, frank, and comprehensive if there is to be hope for a genuinely better future. Economic development is a superb instrument, but only for the short-term. The example of Saudi Arabia tells us that economic affluence does not necessarily lead to democratization. Alone, material wealth is too shallow to support a long-term sustained effort at transforming the collective mindset of societies into a willful pursuit and protection of social and political change that is by definition essential to this enterprise. Economic stability is tightly coupled to market fluctuations, whose cyclic and dependent nature makes them unreliable foundations to support long-term political and social change. What is needed is change deeper in the realm of cultural, national, and religious identity, which subsumes individual identity parameters such as one’s place in the world, relationships with the state, one’s views and perceptions of other peoples, national groups, and religions.

In this first of a two-part series, I argue that the concepts of “Arab World” and “Middle East” are obstacles to the development of the countries and nations involved. At present, they are constructs built from the top down, aimed at imposing an artificially common cultural, political, or religious identity, when instead it would be much preferable to allow a natural evolution towards such common identifiers, when and where possible, from the bottom up. In the second part, I will argue that the linguistic cultural determinant behind these constructs – the Arabic language – has been, and continues to be, a political instrument for cultural and religious domination and a formidable obstacle in the evolution and development of the societies in question into the modern world. In essence, the “Arab World” construct is built on the Arabic language, and the “Middle East” construct is built on Islam.

Contrast these with the concept of “Europe” where the language criterion was first discarded during the late Middle Ages, when Latin became confined to Church matters and the local vernaculars became recognized as the distinct languages of French, Italian, and others. At the same time, the sister concept of the “Holy Roman Empire”, which survived well into the 19th century, was also discarded with the separation of Church and State during the Age of Reason and the Enlightenment. Both were top-down attempts at unity that ultimately failed. Yet, Europe today is moving towards integration, but from the bottom up: By first recognizing and reinforcing local national aspirations and individuality, then allowing them to naturally, gradually, and willfully move toward union or integration into a larger entity. One can draw similar models from the Russian, German, Chinese, and other supra-national entities, but they each are at a different stage in their respective evolutions, and we will limit this discussion to the Arab-Moslem world since it has become the fault line of most conflicts in our time.

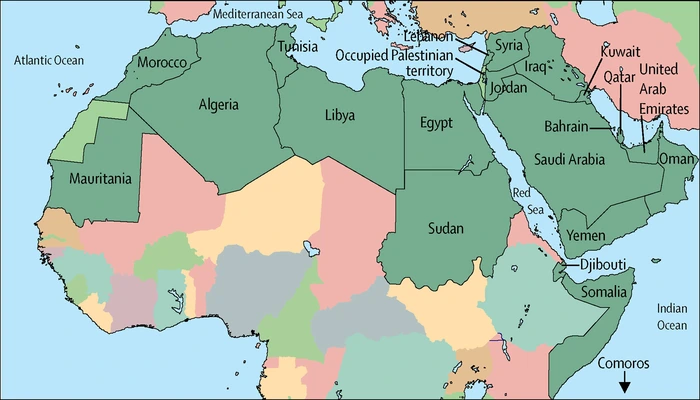

The problem is defined as follows: There are two unchallenged, but in my opinion, false premises that are used today to describe widely diverse groups of nations and peoples. The first is that there exists, somewhere between the Mauritanian coast of Africa in the West, the Persian Gulf waters in the South, and the south Caucasus region at the North, an entity called the “Arab World” that is, however, never defined by any of the standard cultural criteria except perhaps by the very tenuous linguistic criterion of the Arabic language. Overlaying this construct is yet another unchallenged but equally false premise, and that is the existence of a region called the “Middle East” which encompasses the “Arab World” but goes on to include another widely diverse set of nations and societies for, again, no obvious reason other than perhaps the very tenuous religious criterion of Islam.

Some of the features of the “Arab World” and the “Middle East” are:

They are colonial in their genesis, coined by Western Orientalists – both academic and military – who always over-simplified the “other” because they could not comprehend its complexity and in their desire to rationalize it for themselves. Even if colonial in origin, these two constructs have been accepted by the ruling elites – intellectual, religious, or feudal – of the countries, nations, and states that are lumped together in them, even as these elites decry the residues of colonialism.

The “Arab World” construct rests on the false premise of the existence of a “common” language, the Arabic language. The reality is that Arabic has been forcibly and artificially imposed and perpetuated for imperialist religious reasons, always overlaying an existing language that accommodated Arabic to a certain extent, but which was denied its right to naturally emerge as an independent language worthy of codification and official recognition. Much as Latin was imposed in Europe by the Church for religious reasons, then was used for centuries by the ruling elites of Europe to maintain their power in collusion with the Church.

The “Middle East” construct is itself based on the political assumption that lands where Islam dominates must therefore be of one political persuasion. Anything that does not fit the mold is ostracized as self-hating, isolationist, or a “pawn” of the West.

Unless they are abandoned by both insiders and outsiders, and a more decentralized view is adopted that recognizes the individuality of each of the constituent nations, societies, and states, these constructs will continue to hamper the natural evolution of the “Arab World” or the “Middle East” into modern states.

Contrary to the elitists’ desire to forcibly unify these regions from the top down by means of outdated ideologies (e.g. the Fertile Crescent of the Syrian Social National Party, or the Pan-Arab Nation of the Baath Party) that are more reminiscent of the Germanification of Eastern and Central Europe or the Russification of the non-Russian nations of the Soviet Union, the international community should encourage decentralization and the emergence of truly distinct, sovereign and independent states that may, emphasize “may”, subsequently rationally and deliberately enter into unions or federations, much in the same way as the European nations are doing after millennia of warfare and violent supra-national empires. It is only after Monaco, Lichtenstein, Andorra, San Marino, Malta, and Luxemburg have been recognized as equal nations to Germany, France, and Italy that Europe is today able to enter into union.

Behind these two challenges are two equally bad positions: On one hand, the elites of the Middle East and the Arab World agree to these premises for demagoguery and populism, and on the other hand, Western observers and media who simplify their jobs by agreeing to these falsely agglutinating premises. This combination is at once harmful and condescending because it denies a fundamental principle, namely that successful political super-national structures (e.g. European Union, American federalism, Swiss confederalism, etc.) have succeeded because they were from the bottom up and not from the top down. Meaning that these structures evolve and come into being after, and only after, their constitutive elements (nations, states, etc.) have affirmed, strengthened, and obtained formal recognition of their own local identities over some time. These identities could have linguistic, religious, historical a plethora of other reasons, but the basic idea is that these identities have been allowed to thrive and are formally and officially recognized. Only then do they deliberately and willfully, cross the religious, historical, and linguistic barriers that they first erected, and seek integration with other similar entities into larger structures that bring about economic freedom and stability, while preserving their non-economic (religious, historical, linguistic) raison d’êtres.

This opinion was originally published in the November 2003 issue of L’Orient-Express (Vol.1 – no.4), Québec, Canada.