(Note: At the time of this posting, in 2024, the invasion of communications by the social media has somewhat altered the general premises of this article, which was originally written in 2003, by lifting obstacles and enabling young people to communicate in their local vernacular languages for several reasons: they do not master formal Arabic which is not the language they were born with; they find it more natural to express themselves in their native language; and they are increasingly dropping the Arabic script when communicating on social media and replacing it with the Latin script. The future of formal standard Arabic is uncertain.

In the first part of this two-part series (L’Orient-Express, Vol. 1, No. 4, November 2003), I argued that the concept of the “Arab World”, based exclusively on the criterion of the Arabic language, and the concept of “Middle East”, based on the religious criterion of Islam, are over-reaching and artificially created by Western Orientalist thinking, and exploited by indigenous demagogues and oligarchic regimes, and ultimately are the most formidable obstacles to the natural development and evolution of the countries, nations and peoples subsumed under them.

In this second part, I argue that the linguistic cultural determinant behind the Arab World construct – the Arabic language – has been and continues to be a political instrument for cultural and religious domination. With its genesis in the religious justification that Arabic is a “holy” language through which God chose to deliver his final message to the prophet Mohammad, the modern-day corollaries of the preeminence of Arabic are absurdly oppressive and of imperialist vintage destined to maintain the supremacy of Arab over non-Arab Muslims and are therefore counter to evolution and advancement of the constituent societies.

One such corollary is that Arabic is the compulsory language of prayer by Muslims everywhere – including non-Arabic speaking people – with all the hindrances and sometimes dangerous oversimplifications of religious concepts that obtain from praying in a foreign language that is completely alien to one’s daily life.

Another corollary is the forbiddance of translating the Qur’an into other languages, the absurdity of which is evidenced by the fact that it is non-enforceable and actually tolerated: The Qur’an must be translated into the native tongue of the faithful if it is to be comprehensible to non-native speakers of Arabic.

Yet, these edicts remain in place, and as stated earlier, their historical objective was to maintain the supremacy of the Arab ethnic group over non-Arabs in the conquered realm of Islam during the Fath Al-Islami (the Islamic Conquest) between the 7th and the 9th centuries. Today, and in the so-called “Arab World”, the religious supremacy of Arabic has resulted in the development of diglossic societies in which Arabic is a language of formal speech that overlays the local languages and vernaculars of the concerned peoples and societies.

How does Arabic serve to dominate and oppress others? For one, only the educated and religious elites are able to use this language, which is rather difficult to learn and maintain since one does not use it in one’s daily life. Arabic in the “Arab World” is the language of formal settings (Academic instruction, the press, television and the media, and political speech, among others). In the linguistic wars and politics of Lebanon, for example, it is forbidden by law to use the Lebanese vernacular language in the media (say, in a news program) and the use of Arabic is mandated by law, although many independence-minded media outlets have in recent years (post-2003) ignored this Fascist edict. But the supremacy of Arabic remains in place, and the Lebanese language recedes into the background in those areas and activities that impact politics, power, and civic society, that is, areas that create order and bind members of society into a political whole. In contrast, the local language (in its various dialects) becomes the channel of expression for people’s personal and family lives, folklore and humor, theater and poetry, all of which reinforce communitarianism and segregation of society into its religious and ethnic communities.

Again, using Lebanon as an example, Arabic poetry is practiced and admired by the educated circles of the elites, whereas Lebanese language poetry (Zajal) is used to reflect on village life, courtship, love and the feelings of the underclass. The Lebanese vernacular would, if allowed to freely express itself politically, become a powerful tool of unity and a major agent of change, especially in the relation of the individual citizen with the State. The linguistic segregation of Arabic for politics, the media, and State affairs on one hand, with the relegation of the Lebanese vernacular to people’s personal lives on the other hand, says to people that politics, the media and power belong to another realm than their daily lives.

Indeed, Arabic becomes a psychological barrier for ordinary citizens who may try to access political power. It is virtually impossible for a Lebanese politician to deliver a political speech in the Lebanese vernacular and be taken seriously. It is an absolute must that a “serious” political speech be delivered in Arabic, even though people’s concerns would be better conveyed when debated and discussed in their own living language. Which is why, again in Lebanon, political power tends to remain in the hands of the traditional elites, namely the feudal and tribal families, the Church and the Mosque, and the business and media elites. While not the exclusive tool of domination, Arabic is by far the most visible vehicle of that domination. The process of natural democratization becomes severely hampered by the fact that ordinary people, the common man and woman, cannot use their own language in their political lives. The imposition of classical Arabic creates in the minds of people an artificial barrier to the world of politics which they consider beyond their reach, when the fundamental requirement of a democratic society is the active participation and access by the constituency in the political process.

In many ways, the history of Arabic as an instrument of exclusion from political power is identical to the history of Latin, intertwined as it is with the history of the Catholic Church and its use of Latin to maintain power in the hands of monarchs, the nobility and the Church for many centuries. Until the Reformation movement, the Enlightenment and the revolutions of the 15th through the 19th centuries discarded the role of religion in civilian life, Latin was the great separator between the elites and the people. After holding on to Latin for centuries, even as Latin was becoming a dead language and the grassroots were eroding from under it, the Church finally and reluctantly abandoned Latin at Vatican Council II in the 1960s and allowed mass and other rituals to be conducted in the “vulgate” or vernacular languages. Latin gave way in church rites to French, Italian, English, German, Spanish and other languages at the same time that the Church was losing its claims to political power. After having held as blasphemous the printing of the scriptures and their translation into the vulgate languages, it took the Church several centuries before relinquishing the power it held by way of Latin. Some hardcore conservatives in the Church still want to restore Latin as the sole language of Catholic mass.

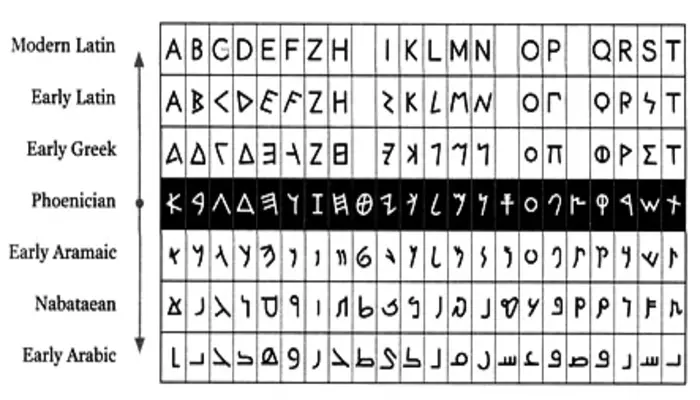

During those centuries (15th-19th), the local languages evolved by the hybridization of Latin with pre-Latin languages (e.g. Celtic among others) to emerge as independent, well-differentiated languages like English, French, Spanish and so on. Indeed, it was the recognition and promotion of these local languages as national languages that accompanied the emergence of the nation-states of Europe. For example, the people who lived on the soil of what will ultimately become the French nation gradually came to see themselves as citizens of a French monarchy and not of the larger Holy Roman Empire of Charlemagne. In time, the French people even abandoned the monarchy as a colluding entity with the residual powers of the Church and began to see themselves as citizens of a republic in which they were able to conceive their lives outside the empire of the Church. Latin was no longer the compulsory language of religion, literature, and science. This evolution naturally climaxed in the separation of state and religion, a concept that remains alien to Islam, with timid and tentative exceptions like Türkiye. Obviously, language is not the sole criterion for defining a national identity.

In addition, and with the Reformation in Europe, the idea evolved of a personal and direct connection to God, as opposed to the necessary intercession of a representative, i.e. the priest. Under the Latin mode, and since most people did not know Latin, one needed the priest to pray and be forgiven, as if God understood only Latin. Under the post-Latin mode, one could pray in one’s own language and directly communicate with God. The Reform movement in Europe was arguably in tandem with the de-Latinization, both cultural and linguistic, of the Church.

Therefore, I propose that one of the sine qua non requirements for the principle of separation of religion from state to take root in Muslim societies is the abandonment of classical or formal Arabic as a primary or official language in those societies. In a most successful precedent, perhaps the only one, of secularization of a Muslim state, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk abolished the Arabic script and commissioned a team of academicians to replace words of Arabic import with words of Turkish roots. Arabic stayed in its right place, to be confined as the language of prayer and rituals, but no more. This is an example that would have to be replicated across the Muslim world, whereby Arabic is relegated to religious affairs while local languages or vernaculars are codified as independent self-standing languages to be used in all aspects of civilian and political life. Only then will people feel they are integral participants in the construction of their societies.

For the linguist and biologist like myself, there is an appreciation for the fact that words of a language evolve pretty much like genes of a genome, by duplications, mutations, deletions, borrowings, rearrangements and other chemical, mostly random, acrobatics. A word is to a language what a gene is to a genome. New words come into existence in accidental and random borrowings from other words (both within a language and across languages). Then they may either be adopted by natural selection or are discarded if unused or untuneful. If a word confers some advantage to its users, such as conveying a meaning for a nameless concept, or if it allows a differentiation between closely related concepts, it is selected by a process of usage-based elimination, and thus becomes part of the language. Once a word achieves success in this fashion, it may generally acquire a slight modification in structure (spelling, pronunciation, etc.) and/or meaning. This is very much how genes evolve as well. Over long periods of time, one way that new genes arise from pre-existing genes is by accidental duplications caused by error-prone DNA-copying enzymes called Polymerases. If the new copy of the gene confers selective advantage (or at least does no harm) to its carrier, it becomes established in the germ line and propagates in the population’s gene pool. As it spontaneously mutates over generations, the second gene will code for a protein that is different in structure, and most likely in function, from the original gene-protein complement.

By imposing an immutable, and for all practical purposes a dead (since no one speaks it natively) language like Arabic on people’s lives, a widening gap and an increasing tension arise between the natural tendency for change on one hand, and the rigidity of an ancient language whose strict religious roots force it to be recalcitrant to change on the other hand. When a few idealists in the post-World War II era wanted to create a unified world, they designed a new language called Esperanto that was supposed to be a universal common language to all people. The idea was that one language would unify the world, just as apologists for one “Arab world” and one Arabic language argue today. However, no sooner that Esperanto was taught in countries far and wide across the globe that it began to naturally evolve in different countries by mutating and differentiating. Like the idea of an artificial universal language such as Esperanto, Arabic is doomed over time. On the heels of the British empire, English is today undergoing such a process of differentiation into several different languages. One can see the widening gaps in English as it is spoken in England, Scotland, the Unites States, India, Australia, Jamaica and others. Similarly Haitian creole has been codified as an independent language that is different from its original French.

The existing conflict between on one hand a coercively unifying language like Arabic, imposed from the top down by rigid religious edicts, and local languages of peoples and nations scattered across large widely diverse geographies and cultures, must come to an end. To do that, linguists need to codify the local vernaculars, i.e. formalize their grammar and syntax, and let them become independent languages. For example, the Lebanese vernacular has roots in the Aramaic-Canaanite-Phoenician heritage of the country, with imports over centuries from Greek, Latin, Arabic, Turkish and Persian. The Lebanese language has never been formally codified and its rules of grammar and syntax have never been taught in schools, although researchers like Wheeler Thackston has produced, as far as I know, an unpublished but detailed manual of Levantine Arabic grammar. Lebanese children learn Classical Arabic at school but speak Lebanese in their everyday life. Western students of Arabic face a monumental task of learning Classical Arabic to be able to read and write, and one vernacular language like Egyptian or Lebanese or Moroccan etc. to be able to function in the corresponding country. That difficulty alone makes learning Arabic a formidable task and may in fact be the main reason why the “Arab world” remains immune to development and integration into the modern world. Diglossia is a major barrier to access a culture.

I am often stunned by how intellectually distant Classical Arabic is from the people it is supposed to serve. The diglossic nature of life in the “Arab world “ is such an anomaly in our time. The average person may hear Classical Arabic (say, in a news broadcast) but does not actually internalize it during the listening process. Its formality and distance from daily life handicaps its ability to express specific nuances and shades of meaning, and rather becomes pre-packaged quanta of information that are repeated over and over in political speeches and the media with little input of individuality by the speaker and with even lesser import to the audience.

Like Quebec, Ireland or Belgium, Lebanon struggles with disparities between a language perceived to have been imposed by an invader and the local indigenous language. On the one hand, the native population of Lebanon in the 7th century AD spoke Aramaic when the invading Arabs arrived. Aramaic had been already overlaid the Greek and Latin of the Hellenic-Roman empire to which Lebanon belonged for centuries since 333 BC when Alexander the Macedonian conquered the Phoenician coast.

Arabic gradually supplanted Aramaic, primarily in the cities along the coast. But in no simple terms, and only because of the political ramifications of life under Islam, and not because of the integration of Lebanon into the broader Muslim world. After all, only the cities were Islamized because the Arab armies did not venture up the rugged mountains to convert their inhabitants. Many of these inhabitants had been seacoast dwelling Phoenicians who first escaped brutal Christianization at the hands of the newly converted Romans-Byzantines by running for the mountains. When the Muslim Arabs arrived in the 630s, those Aramaic-speaking Christianized Phoenicians were able to resist conversion to Islam. Which is why today’s Lebanese mountains are largely inhabited by Christians (Maronites) and by non-Sunni Muslim populations (Shiite Muslims and Druze). The gradual takeover of Arabic took place over the next centuries not by a process of replacement but by one of hybridization between Aramaic and Arabic, a process facilitated by the fact that these two languages are closely related Semitic Languages. A similar process is occurring in Palestine-Israel, where the Palestinian vernacular and Hebrew are experiencing similar shifts.

The imposition and survival of Arabic as the language of the Lebanese elites was merely the result of the proximity of Lebanon with the center of gravity of Islam in nearby Arabia. This is unlike places like Armenia or Ireland which managed to maintain intact their native languages despite their adoption of the invader’s language (Celtic in Ireland, Turkish in Armenia) because one is a mountain (Armenia), and the other is an island (Ireland).

The Arabs stayed in Lebanon from the mid-600s AD until the Crusaders arrived in the 11th century. When the latter left 2 or 3 centuries later, the non-Arab Mamluks took over during the 14th and 15th centuries, followed in 1516 by the non-Arab Ottoman Turks who stayed until 1918, and finally by the French under mandate from the League of Nations between 1919 and 1943. Overall Lebanon was under Arab rule for about 4 centuries, which diminishes the claims of Lebanon’s “Arab” identity.

Ultimately, the “Arab World” and “Middle East” constructs, as well as the role of the Arabic language, have had serious negative implications on the evolution of the various nations and ethnicities that are arbitrarily lumped together. As language is a major – albeit never the sole – determinant of cultural identity, a de-emphasis of the illusion that Arabic is the glue that holds the “Arab world” together would be a most welcome process. In parallel with political tools such as decentralization, self-determination, autonomy and other forms of local governance, the recognition of nations, ethnicities, religions and linguistic groups as self-standing entities would be central to lay the foundation for stronger and grassroots participation in building a better future for the region concerned. There are voices today, as there have been since the fall of the Ottoman empire, calling for a united “Arab world”. But this idea remains premature at present because of the absence of political maturity and a lack of understanding of what a union entails. The experiment of uniting Syria and Egypt into one United Arab Republic in 1958 failed miserably within a year of its inception because it was improvised and impulsive and not resting on solid foundations, in contrast with the European Union which has taken several decades and has yet to mature. Decades after the end of western colonialism, Arab countries have yet to liberate themselves and undergo an “internal decolonization” (as the Syria dissident calls it) and promote centrifugal trends within their societies. Once established in this first stage, the resulting independent and well-recognized nations, countries and other political entities can embark on the second stage consisting of laying down a path for integration, federalism, and maybe even union where warranted. All successful models (US, Switzerland, Germany, United Arab Emirates, European Union) remain based on a willful and reversible decision by the constitutive element, whereas all attempts at a forced top-down union (Nazi Germany, United Kingdom, Soviet Union) have generally failed throughout history.

There are two periods in contemporary history that are used by the pan-Arab apologists as models for unifying the “Arab World” or parts thereof:

- The pan-ethnic nationalistic movements of the 19th and early 20th century, including Pan-Turkism, the Communist Soviet empire, the Fascist and Nazi movements in Italy and Germany and such other racial supremacist ideologies. From these examples, some in the ”Arab world” have borrowed the Pan-Arab nationalist ideology of the Baath Party (founded by Michel Aflaq) in Syria and Iraq, or the Pan-Syrian Social Nationalist Party (founded by Antoun Saadeh) in Syria and Lebanon. Both were, and remain, essentially Fascist ideologies claiming the supremacy of one “ethnic” group over other groups which must therefore be suppressed. The Baath ideology claims advocates the superiority of “Arabs” over Westerners and other groups living within the confines of the so-called “Arab World”, and aims to unify, by force if need be, all these people under an Arab identity. The Pan-Syrians for their part seek to unify all the Northern Semites in a so-called Fertile Crescent geography on the racist premise that excludes the peninsular Arabs as inferior and less civilized than the “Syrian” inhabitants on the northern border of the Arabian Peninsula. Since both were founded by Christian ideologues, they claim to be secular and are evidently motivated by rejecting Islam as a foundation of identity.

- The more recent model of the European Union with implications for the creation of a Common Arab Market, which could potentially be a useful model, but only if two conditions obtain:

- A united Europe is now possible after more than a thousand years of warfare and mayhem in Europe, only after the formal recognition of local sovereign national identities ranging from large entities like Germany, France or Italy (themselves aggregates of smaller identities that were glued together during the 19th century) down to tiny Lichtenstein, Andorra, Monaca, Luxemburg and San Marino. So, it must be for the “Arab World”: Unless Lebanese, Syrians, Alawites, Palestinians, Maronites, Druze, Assyrians, Armenians, Kurds and others are recognized as national, religious, linguistic or ethnic but sovereign entities that are first allowed to thrive on their own, they will continue to resist coerced integration into a larger Sunni Muslim-dominated Arabia or Syria. Such an integration may initially happen for economic and other pragmatic but not ideological reasons, and only if the rights of individuals and groups are not only protected as “tolerated” (Dhimmi) minorities, but are strenuously defended and enforced.

- In order for the above to actually happen, the languages of the region must be liberated from the yoke of a dead and archaic Arabic language that is unable to keep up with the explosion of technological change, and whose destiny one day is to become the object of interest by specialists in dusty old libraries, as has been the case with Shakespearean English, Gothic German and Latin in Europe. The “Arab” individual must be liberated from the shackles of the language of the invader, a language that people neither use in their daily lives nor are born speaking it, a language that is codified but not lived, and a language that finds its origins in a religious and violent conquest of some 1,300 years ago. Local languages must be allowed to be formalized, codified and used as national languages while Arabic must be relegated to academia and religious madrassas. [For example, Professor Wheeler Thackston of Harvard University has codified the syntax and grammar of the Levantine language). The doors must be opened for people to express themselves in their own languages in order for the average individual to access power, affluence, and economic freedom. As in Europe where the Dutch speak Dutch and not a form of German, and the French speak French and not a form of Latin. It is through this process that took several centuries to materialize that the members of the European Union have deliberately and willfully agreed to come together, all the while maintaining their distinct and independent characters, rather than being forced into a union as subjugated minorities to an imperial and hegemonic Europe.

This commentary was originally published in the December 2003 issue of L’Orient-Express (Vol.1 – no.5), Québec, Canada.